Webster defines photojournalism as the “photographic presentation of news stories or stories in which a high proportion of pictorial presentation is used.” I could find no definition for photojournaling as I believe I’ve concocted the word to apply to a new artistic endeavor. We are all familiar with the various ways nature photographers and nature writers present their work.

Great photographers provide great images, mostly with short captions or identifying text and an accompanying essay by a well-known writer. The captions often interpret what is viewed within the image. Upon occasion photographic books have images accompanied by excerpts, quotes, and other text from the historical literature. These are meant to inspire by the use of both types of imagery.

Nature writers who rely on only the written word to describe nature and natural phenomena must enter into great detail, describing colors, shapes, relative positions, and overall landscape elements that would be readily evident in a photograph. In this instance the old adage about a picture being worth a thousand words is likely to be true. It simply takes time and words to “create a picture” in the reader’s mind.

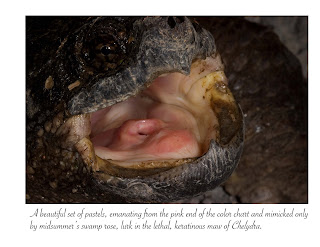

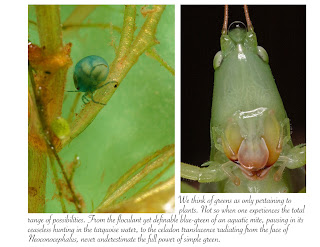

So, what exactly is photojournaling and where does it fit into this overall picture? Photojournaling, if I had to define it, is somewhere between all of the above and involves visual images that enlighten, depict, and portray features and organisms in the natural landscape, but fail to complete the entire “aesthetic picture” the individual seeks to portray. The images should be strong enough to negate the need for much explanatory text, yet benefit from the written observations of the photographer. These images basically originate from a “clear mind,” one free of the need to create lengthy descriptive text on what has already been portrayed in the image. In short, these observations can serve to complete the imagery began in the photograph, can even serve to anthropomorphize the subject matter, or create a complete aesthetic picture of an image or series of images.

As a scientist, I have been taught to steer clear of any kind of anthropomorphizing in my research and written words about science, but I’ve found as a photographer, relating what may be viewed as stark nature to the human condition can instill a sense of wonder and enjoyment in the viewers. We all know this is the first step toward developing an engaged public and is the first and perhaps most important step in developing a conservation ethic.